Rebuilt Gdansk reflects history

By HAL PIPER

Sun Staff Correspondent

Gdansk, Poland—In college, Romuald Chomicz, the conservator of Gdansk’s historical monuments, studied gentle subjects like art history and the chemistry one would need to know to analyze and restore precious objects,

But defending Gdansk from well intentioned developers, he finds, is a politicians job.

Mr. Chomiez does not lose often. “I understand that we need modern roads,” he says, “but we have important monuments all over the city. I cannot let them move a monument just because the roads need widening.”

Then there are the visions of “certain strong-minded young architects.”

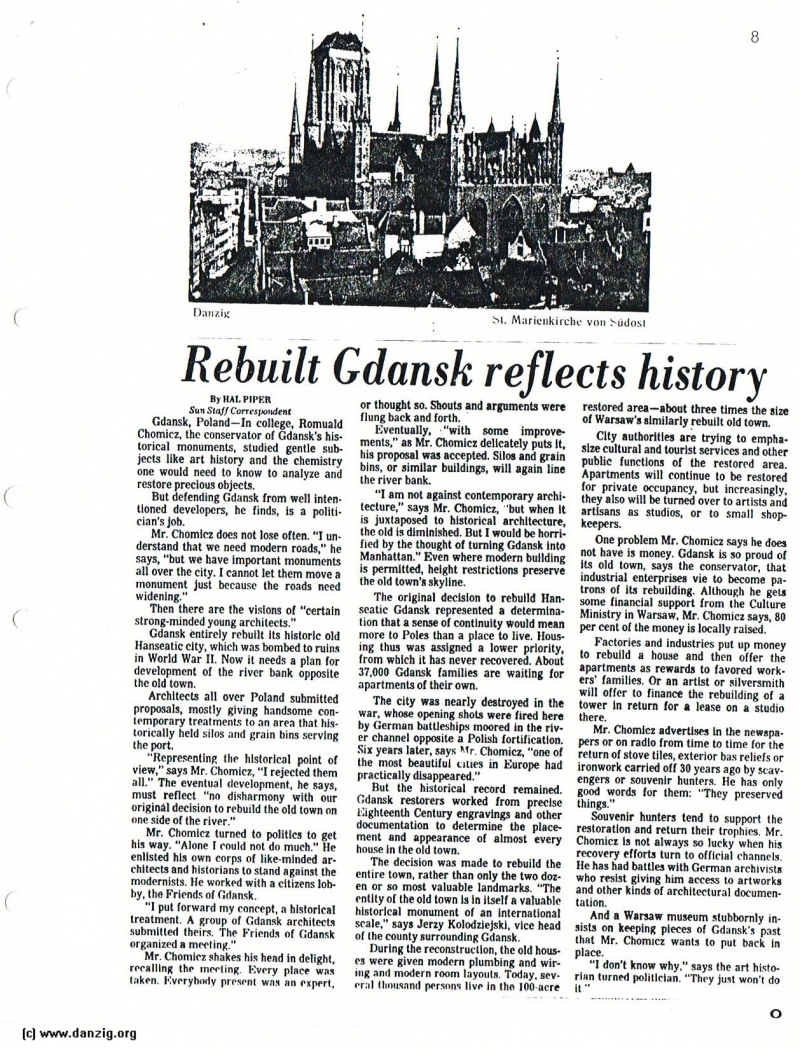

Gdansk entirely rebuilt Its historic old Hanseatic city, which was bombed to ruins in World WarI Il. Now it needs a plan for development of the river bank opposite the old town.

Architects all over Poland submitted proposals, mostly giving handsome contemporary treatments to an area that historically held silos and grain bins serving the port.

“Representing the historical point of view,” says Mr. Chomicz, “I rejected them all.” The eventual development, he says, must reflect “no disharmony with our original decision to rebuild the old town on one side of the river.”

Mr. Chomicz turned to politics to get his way. “Alone E could not do much.” He enlisted his own corps of like-minded architects and historians to stand against the modernists, He worked with a citizens lob by, the Friends of Gdansk,

“I put forward my concept, a historical treatment. A group of Gdansk architects submitted theirs. The Friends of Gdansk organized a meeting.”

Mr. Chomiez shakes his head In delight, recalling the meeting. Every place wan taken. Everyhody present wan an expert, reflects or thought so. Shouts and arguments were flung back and forth.

Eventually, “with some improvements,” as Mr. Chomlcz delicately puts it, his proposal was accepted. Silos and grainbins, or similar buildings, will again line the river bank.

“I am not against contemporary architecture,” says Mr. Chomicz, but when it is juxtaposed to historical architecture, the old is diminished. But I would be horrified by the thought of turning Gdansk into Manhattan.” Even where modern building is permitted, height restrictions preserve the old town’s skyline.

The original decision to rebuild Hanseatic Gdansk represented a determination that a sense of continuity Would mean more to Poles than a place to live. Housing thus was assigned a lower priority, from which it has never recovered. About 37,000 Gdansk families are waiting for apartments of their own.

The city was nearly destroyed in the war, whose opening shots were fired here by German battleships moored in the river channel opposite a Polish fortification. Six years later, says Mr. Chomicz, “one of the most beautiful cities in Europe had practically disappeared.”

But the historical record remained Gdansk restorers worked from precise Eighteenth Century engravings and other documentation to determine the placement and appearance of almost every house In the old town.

The decision was made to rebuild the entire town, rather than only the two dozen or so most valuable landmarks. “The entity of the old town Is in itself a valuable historical monument of an international scale,” says Jerzy Kolodzlejskl, vice head of (he county surrounding Gdansk.

During the reconstruction, the old houses were given modern plumbing and wiring and modern room layouts Today, several thousand persons live in a 100-acre history restored area-about three times the size of Warsaw’s similarly rebuilt old town.

City authorities are trying to emphasize cultural and tourist services and other public functions of the restored area. Apartments will continue to be restored for private occupancy, but increasingly, they also will be turned over to artists and artisans as studios, or to small shopkeepers.

One problem Mr. Chomicz says he does not have is money. Gdansk Is so proud of Its old town, says the conservator, that industrial enterprises vie to become patron.s of Its rebuilding. Although he gets some financial support from the Culture Ministry in Warsaw, Mr. Chomicz says, 80 per cent of the money is locally raised.

Factories and industries put up money to rebuild a house and then offer the apartments as rewards to favored workers’ families. Or an artist or silversmith will offer to finance the rebuilding of a tower in return for a lease on a studio there.

Mr. Chomlcz advertises In (lie newspapers or on radio from time to time for the return of stove tiles, exterior has reliefs or ironwork carried off 30 years ago by Scavengers or souvenir hunters. He has only good words for them: “They preserved things.”

Souvenir hunters tend to support the restoration and return their trophies. Mr. Chomicz is not always so lucky when his recovery efforts turn to official channels he has had battles with German archivists who resist giving him access to artworks and other kinds of architectural documentation.

And a Warsaw museum stubbornly insists on keeping pieces of Gdansk’s past that Mr. Chomicz wants to put back in place.

“I don’t know why,” says the art historian turned politician. “They just won’t do it."

Danzig Report Nr. 19 – May - June - July - 1978, Page 8.

Hits: 3323

Added: 06/06/2015

Copyright: 2025 Danzig.org